|

Stay put or upgrade OS? There's a distinct difference between upgrades and updates; upgrading means a whole new OS version, whereas updates are adjustments to the OS version in use. Both are available via the App Store (in Apple menu).

NOTE: We suggest turning OFF auto-update in System Preferences/Settings > Software Update - including checkboxes lurking under Advanced button. Check for updates manually, as needed and on your schedule.

Updates are generally quick and a good thing. Upgrades however, can be problematic, should never be interrupted, and can take some time. In either case, installations should always be preceded by a full backup.

Some research may be helpful regarding specific machine (CPU), critical software in use and OS compatibility. Most updates may be installed as they become available, but an OS upgrade can result in obsolete apps and device drivers, may include include RAM requirements and adequate storage space. OS 10.15 Catalina was the last OS native to Intel CPUs, Big Sur and later requires an internet connection. Again, a complete backup prior to making any significant change is highly recommended. Other general suggestions:

Graph above shows versions of Mac OSX on Intel processors (CPUs). Ancient CPU History:

MacOS 10.6.8 was required prior to upgrading to 10.7 thru 10.9.

Minimum OS 10.7.5 was required for upgrade to 10.11 El Capitan. Minimum 10.11 was required for upgrade to 10.12 Sierra.

10.13 High Sierra is required for Solid-state drives (SSDs), and is required for upgrade to 10.15 Catalina and later. OSX (10.x) ended with the advent of "Apple silicon" (the M1, M2 and later processors). Newer OS versions are designated as OS11, OS12, OS13, OS14, OS15 - then we jump up to OS26 (Tahoe).

10.10 Yosemite Tech Specs and Requirements

10.11 El Capitan Tech Specs and Requirements 10.12 Sierra Tech Specs and Requirements 10.13 High Sierra Tech Specs and Requirements 10.14 Mojave Tech Specs and Requirements

10.15 Catalina Tech Specs and Compatibility Also see: Apple - How to Update your Mac (newer OS versions). Direct links to MacOS downloads are posted on our All Things Apple page, from OS 10.8 thru 10.15 and beyond - but - don't be surprised if Apple prohibits access or links have gone extinct.  OS 10.14 Mojave Apple made the decision to switch from rotational drives (HDDs) to solid state drives (SSDs) around 2013, along with a revised drive format (APFS). OS 10.13 High Sierra made the transition and runs on either drive type with either format (HDDs should have HFS+/MacOS Extended).

10.14 Mojave was the first OS designed for SSDs using the APFS format, and was the last OS before added security 'features' complicated many things. Mojave can still run older apps BTW (like Adobe CS5) on an APFS formatted SSD.

While Catalina will operate on an HDD using the older HFS+ format, performance may begin to decline over time and is not recommended. New security protocols also affect performance on rotational HDDs. For this reason, upgrading to Catalina on older Macs should include upgrading machine's drive to Solid State (SSD).

|

Recent Macs Click here to find out what OSX version shipped on your Mac and which build is recommended. (Build info may be found under Apple menu > About this Mac, then click on "version 10.x.x" to toggle between version, build and machine's serial number.

PRAM batteries: The first-ever Mac (1984 128K) used a fat-diameter AA-length battery in an external battery box with a door; a modern, full-size AA 3.6v lithium battery works quite well in 128K Macs with room to spare.

Apple ][s and other early Macs used 3.6v 1/2AA lithium battery - except that they were usually soldered to the logic board. Best solution for these is to install a battery box inside these machines where battery was located. A common 3.6v lithium battery can also be used to replace those weird, square 4.5v batteries found in old Performas. Connectors: First 128K and the 512K "FatMac" (that came with "more memory than you'll ever need") used an RJ-11 plug to connect keyboard, commonly known as a phone jack. Coiled cable to keyboard was identical to those on telephone handsets of the day. The mouse, however, used a strictly proprietary connector. When hard drives came along, Macs used SCSI drives, including an external drive port, with serial ports for printer and modem connections.

Floppy drive mechanisms may need cleaning and a little oil as they tend to get sticky over time (critical for first Macs lacking hard drives). Assuming hardware is intact and new PRAM battery is in place, your next challenge is to obtain and install the best OS appropriate to CPU's age.  Early Operating Systems (on 400K, 800K diskette) Back in the old days of 128K Macs, the 512K "Fat Mac" and other early Macs, we had no need of System version numbers and names; the Mac's OS was simply known as, well, the MacOS. Back then, both the Operating System and application programs fit nicely on a single 400K "floppy" (actually the first 3.5" hard-shell Sony diskette that would become industry standard), with just enough space left over for a document or two. Hot setup was having two 400K diskette drives.

System 6.0.5 and 6.0.8 (MultiFinder): MacPlus to SE The advent of MultiFinder meant you could have more than one app open at a time. Ancient MacPlus and early SE models with 800K drives can't go past System 6.0.8 without extensive modification to meet minimum System 7 specs. An SE equipped with 1.4MB diskette drive(s) could be made to run System 7.

System 7.5.5: Good choice for 68030 and 68040 Macs, including the SE/30 7.5.5 requires a 1.4MB diskette drive and 8 to 16MB RAM. (System 7.5.5 can gobble up 4-5 times as much RAM as System 7.0 did on 68K machines.) Communications via bulletin boards (BBS) was the norm at that time.

32 MB of RAM and System 7.6.1 _might_ get you online today, but you won't get very far without using Cyberdog or hacking Netscape for use on certain machines like the SE/30. This configuration, System 7.6.1, represents the bare-bones minimum required to allow email and internet on early Macs and PowerBooks. System 7.6.1 also supported the multiple SCSI bus of 603e/604e PowerPC Macs.

Apple used license of this System release to terminate Mac clones. (There were at least six at the time, including Motorola, UMAX and Power Computing.) OS 8 was actually the last of System 7 (unofficially 7.7). The other big change was this: OS 8 was the first MacOS to have a price tag.

OS 8.1 Introduced HFS+ extended format, along with more than a few other significant changes including enhanced software capabilities and communications. 8.1 was the _real_ beginning of the MacOS version 8. Runs on almost all PowerPC Macs up to the G3 Risc series processors (also known as the 750 chip).

Improved interface and control over view functions with global preference settings. 8.5 introduced Sherlock, expanding search capability and indexing. Top end for 603e CPUs. If you can't use OS9 (which will not install on ancient PPCs), 8.5 or 8.6 is best choice.

OS 9.1 will run on 604s, G3s, and a few G4 Macs. Newer G4s and G5s will not startup with OS9, but can run OS9.2.2 and apps using OSX Classic Mode (provided OS9 drivers were included with hard drive format under OSX).

With improved security, data encryption, and many communications enhancements, OS 9.2.1 was the last commercial release of System 9, followed by one final update to OS 9.2.2. Update 9.2.2 contains improved OSX "Classic Mode" compatibility and additional hardware drivers for G4 CD and DVD burners. Last, best browser under OS 9 was Netscape 7.02. OS 9.2.2 is absolutely necessary for "Classic" OS9 apps. Tiger 10.4 was the last version of Mac OSX to recognize OS9 "Classic mode" and legacy software. Leopard 10.5 will not recognize legacy software, nor can Intel machines run legacy PowerPC apps.

Slow, incomplete, not a pleasant experience. OS 10.0 thru 10.2.x are best avoided; any machine capable of running 10.0-10.2 Jaguar should be running Tiger (10.4) or later, if possible.

Officially, all G3s - except the very first (beige) models and the first G3 PowerBook - will run OS X versions thru 10.3.9; in reality, RAM requirements and hard drive space are determining factors. All G4s will run Panther nicely; a few later G4s and all G5 models startup in OS X only, but all machines up to Intel Macs (and Leopard 10.5, below) will run OS9 apps in Classic Mode on drives formatted with OS9 drivers installed. Unofficially, almost any Mac with PCI architecture allowing addition of a USB card can run OSX with a little tinkering.

Written to accommodate the 64-bit G5 processor and newer Intel Macs, Tiger is virtually identical to Panther with a few added bells and whistles, many of which require a broadband connection to the internet (as does the Software Update function built into both Panther and Tiger). All G5 Macs should be running Tiger 10.4.11 or Leopard 10.5.8 (with sufficient RAM).

Early Intel Macs may have shipped with Tiger 10.4 onboard, but upgrading to Leopard 10.5 or Snow Leopard 10.6 will allow the CPUs in these machines to operate at full potential. Later Intel-powered Macs will not run 10.4. Official release was on October 26th, 2007. Apple finally dropped legacy support for OS9 and Classic Mode with Leopard 10.5, regardless of machine's processor (G5 or Intel). Apple claimed "300 new features" when 10.5 was released, but 10.5's real claim to fame is that it is the last OS that will run on G5s and some G4s.

A highly polished version of Leopard, Snow Leopard (OS 10.6) was released a month ahead of schedule. Snow Leopard may have originally been intended to be an upgrade for licensed Leopard 10.5 users, but the 10.6.3 DVD will happily do a full install to an empty drive. Slick, smooth and stable, Snow Leopard had the longest useful life of any OS since OS9.

NOTE: Some machines will not boot from the 10.6.3 DVD as they require 10.6.5 update and later versions to 10.6.8. Requirements were: Broadband, OS 10.6.6+, 2GB RAM, and a Core 2 Duo or later processor. Support for legacy apps and "Classic Mode" was dropped with Lion. More than a few changes came with Lion, including infestation of social networks wherever possible and the advent of "cloud" services.

NOTE: Lion 10.7 was also briefly available from Apple on an 8GB flash drive for $60-70, tho these are long gone (Apple# A1384). Device was also marked 607-9072. OSX 10.8 Mountain Lion: Last o'the Big Cats, $20 download only

Requires: Broadband connection, OS 10.6.8 or later installed, 2GB RAM, 8GB drive space, and appropriate Mac CPU (details here).

"Broadband" back then meant 3Mbps or higher; downloading a 8GB file took 6 hours or more. Updates may also be necessary after upgrading to Mountain Lion, still available from Apple when last we checked. Mavericks was the last MacOS to support dialup. Shortly after its release, Apple popped-out Yosemite to replace Mavericks, which was the last OS build from the Snow Leopard 10.6 family. Apple has long since dropped support for Mavericks.

OSX 10.10 Yosemite: Core2Duo and later CPUs Yosemite was removed from Apple's App Store on release of El Capitan (next), but requirements were about the same: Broadband internet, min. 2GB RAM, and replacement of older apps that are no longer supported. Upgrades/updates to most 3rd-party programs is necessary.

OSX 10.11 El Capitan: Some Core2Duo, i3 and later CPUs

Requires mid-2007 iMac, late-2008 MacBook/Pro, early-2009 MacMini or later models; minimum 2GB RAM (recommend 4GB), other details and specifics available here: El Capitan . 10.11 El Capitan is last OS that many Core2Duo machines will run; these machines will go obsolete after Apple stops supporting 10.11.

Sierra 10.12 specs here: Sierra. Requires late 2009 Mac or later, 2GB RAM required (4GB+ recommended), and minimum OS 10.7.5 to upgrade. This OS occupies nearly 9GB of drive space and is a large file to download - true broadband/fiber recommended from here on out as these System versions will only get bigger.

OSX 10.13 High Sierra: Last OS for early-2012 and older Macs

OSX 10.14 Mojave: Last OS with native 32-bit support High Sierra 10.13 appears to have about the same System requirements as 10.12 Sierra did (with a lot of polish and improvements) and should run on any machine capable of running Sierra. 2GB RAM minimum, 4GB RAM or more recommended, OS 10.13 occupies 15GB of drive space.

Featuring "Dark Mode," Mojave 10.14 System requirements and features may be found here. Apple has decided to extend 32-bit support one last time with Mojave; 32-bit apps launch with a warning that an upgrade to the app will soon be necessary to prepare for the next OS version. More info here. Mojave was the last integrated OS before Apple locked-up the OS on its own partition. 2-4GB RAM required, 13GB drive space (depending on upgrade route).

Catalina Machine Compatibility, 8GB RAM recommended (4GB min), 13GB drive space (depending on upgrade route). All Macs (since Tiger was a kitten) have had 64-bit processors that will accommodate 32-bit apps; support for old 32-bit apps ended with Catalina's 64-bit only environment. Catalina adds some serious new security features, and requires APFS drive format on solid-state drive (SSD). This is the last Intel-native OS and the end of OSX (10.x).

Being the first OS written for Apple silicon, it was bound to have some problems, and sure enough it did. One big example was OS 11's inability to recognize Time Machine backups from previous OS versions; as it turns out, this issue continues to plague later OS 11 updates as well. Requires a minimum 4GB RAM (technically), 8GB RAM or more in the real world. OS 11 BS consumes a whopping 36GB of drive space. Big Sur is best avoided, if possible.

A few older Macs top-out at OS 11 Big Sur OS 11 compatible Macs. Macs with Intel CPUs that are capable of running Big Sur also require Rosetta 2 emulation, which should be automatically installed with OS 11. For Apple CPU Macs (M1 and later) that need support for Intel apps, download is here: Rosetta 2

First polished/finished (and stable) OS for M1 and later Macs, Monterey is a good choice for Intel machines capable of upgrading past OSX. From here on, all apps must be 64-bit, and startup volumes - along with backup drives - must be solid-state with APFS format. OS 12 requires 8GB RAM (min) and 28GB drive space.

OS 13 Ventura: Possible end of data recovery  M1/M2 Macs cannot be upgraded after purchase, with both RAM and drive storage soldered to logic board (aka "onboard"). Ventura requires a 2017 or later Mac, min. 8GB RAM, 25GB drive space, and includes Startup Security features - on by default - that may prevent data recovery by locking out all access (details). Maintaining a current backup is now critical; the combination of security locks and non-removable drive may prevent data recovery should machine suffer any failure.

Touchbar Macs introduced the T1 security chip, replaced with the T2 chip in 2016. The T2 has three ways to prevent a Mac from operating; if all three are active and you lose access to your AppleID, your Mac can be permanently disabled (bricked).

Game Mode, Widgets, emojis, bug fixes, various enhancements, new features and fluff, plus still more Security additions. After install, Sonoma (alone) consumes over 28GB of drive space, uses at least 8GB RAM, and can easily be twice the size of your previous OS, depending on upgrade route. And, as usual, all bugs are removed after numerous updates and the OS is fully polished just in time for the next OS release.

Released in fall of 2024, Sequoia's claim to fame is the inclusion of AI (which Apple refers to as "Apple Intelligence"). Requires T2 security chip; full compatibility requires M1 and later Apple CPUs. OS 15 Sequoia is another behemoth consuming 30GB of drive space, over 8GB RAM, and stuffed with troublesome security features that can - and will - prevent data recovery unless turned off at install.

Released in October of 2025, Apple has decided to skip from OS number 15 to number 26 for no apparent reason other than, possibly, the year (including the new iOS version). Oldest supported Macs: 2019 16-inch MacBook Pro, 2020 MacBook Pros, Airs and iMacs, and the 2022 Mac Studio.

Full compatibility list, courtesy of OWC: Tahoe-compatible Macs

|

Hard Disk Drives (HDDs) These drives come in two physical sizes: 3.5-inch and notebook-sized 2.5-inch. HDDs store data on multiple spinning platters, each having read/write heads. The more platters, the more storage a drive will have. 2.5" drives are typically limited to 2TB capacity, but single 3.5" drives can have over 50TB of storage.

Typical 2.5" internal Hard Disk Drive perched atop a 3.5" internal Hard Disk Drive

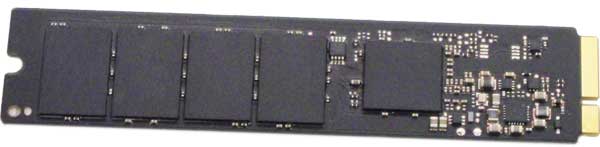

Larger 3.5" drives can be combined into RAID arrays capable of massive storage capacity. At about 5¢ per Gigabyte, hard disk drives are the economical choice for storage and backup needs, where reliability is a greater concern than speed.  Removable blade-type SSD found in older MacBooks

SSDs store data within a massive array of semiconductors (transistors) and operate at nearly the speed of light. Some are available in a 2.5" case designed to mimic a 2.5" HDD and fit into older machines, others are in a compact blade configuration like the one above."Onboard" SSD arrays (last Intel and all M-series):  New Macs have their drive storage in a chip array soldered directly to logic board

Having SSD chips soldered to logic board can make data recovery difficult if not impossible. In the event of a machine failure, unless logic board happens to have an access port (sometimes called a lifeboat port - very rare), data recovery is impossible, as is troubleshooting. Security settings in current OS versions also prevent access ( see our Backup Plans page). Maintain a current backup drive, or be prepared to lose all your data. Meantime Between Failure (MTBF) All (quality) drives are designed to survive a target lifespan under severe operating conditions, but all drives will fail eventually. HDDs can reasonably be expected to last at least 5-years and should be replaced at 10 just by virtue of age. They may exhibit symptoms of pending failure for a time, but failure is usually sudden. The longest warranty on HDDs used to be 5-years, same as SSDs are now, but that's where any similarity ends.

HDDs are subject to mechanical failures, often without warning. SSDs have no moving parts, but they degrade over time, too. Most SSDs are designed to "die" when they reach a predetermined error count or age, defined as meantime between failures. MTBF is typically well beyond normal use, but when an SSD reaches the end of its estimated life, it will cease to operate rather than degrade. Lights out, game over, done. Again, backup = good. Hard Disk Drives (HDDs) may not be the fast choice, but they can't be beat in terms of dollars-per-gigabyte external storage. A 1TB HDD (1000 Gigabytes) can be had for less than $50 and has sufficient storage capacity for most casual users. For so-called "power users" - audio/video editors, graphic designers, sound studios, etc. - storage capacity is a major concern and power users can't have too much.

27" iMac storage could be upgraded, 21" iMacs maxed out with 2TB or 4-5TB (using 15mm HDDs), and notebook machines after 2013 used SSDs. Current Macs cannot be upgraded at all after purchase.

NOTE: If you deal with large files like high-rez photos, broadcast-quality video, or multiple audio files, see Backup Plans & Options page for storage suggestions.

|

What is it, and why do I need more? Adding RAM (Random Access Memory) can be a cost effective and significant upgrade for most computers, especially older ones. Many people confuse RAM with storage space on a drive, but they're two very different things. RAM is where work takes place; when you startup your Mac, its Operating System loads into RAM. When you launch a program, it also loads into RAM. RAM is where creation, editing and all work takes place; data is then written to storage on your HDD or SSD drive when saved.

While working, RAM is shared between OS and apps. On shutdown, RAM is emptied. If power is interrupted, whatever was in RAM will be lost (unless saved), but data stored on your drive should survive unaffected. More RAM means faster processing and allows more applications to be open and running simultaneously. If you use your computer for more than simple word processing and email, you will likely benefit from adding RAM.

NOTE: New Macs cannot be upgraded after purchase - period. See Upgrade or Replace page for more info.

Memory (RAM) types RAM modules, sometimes referred to as DIMMs (Dual Inline Memory Modules), come in a variety of sizes, types and brands, with various technical specifications and physical configurations. RAM is always machine-specific; sometimes a RAM module can be moved from Mac to Mac within a machine "family" (i.e. same processor and bus specs), but this is somewhat rare. DIMMs are keyed to fit into matching RAM slots.

Research your machine's requirements by checking your System Profile, or by researching machine's serial number (usually found under iMac stand or printed on bottom of notebooks). Match these specs to memory from reputable vendors.

RAM issues can bring down the entire system, lockup machine, and cause all sorts of nonsense (usually cured by removal). Inadequate, mismatched or out-of-spec RAM will prevent startup and cause the machine to issue a series of beeps. If an application was properly written, there will be a subroutine that periodically checks memory management and will utilize a block of drive space temporarily if needed. Otherwise, programs may freeze, hang or quit without warning, or machine might stop responding to input. If you experience spinning beach balls for extended periods or apps unexpectedly quit, you might need to add RAM or quit unused apps to free-up memory.

Your Operating System requires a fair amount of memory all by itself, increasing with each new OS release. Modern System versions typically use 6 to 8 GB RAM, possibly necessitating a memory upgrade when upgrading OS versions.

|

Consider a web site (if you don't have one) Life in the "Information Age" means searching the web for anything and everything; people expect to find info about you and/or your business on the internet. Web sites are like an online business card, only better. They can include examples of your work, answers to common questions, inventory, photos, videos, a map and all sorts of info beyond just a phone number and address.

Registering a domain name, designing a web site and posting it with a web host can take a bit of doing, but once established, a web site can be an essential advertising and marketing tool - or just a fun place to share things with friends and family. You can have your own blog or discussion group, post photos, slide shows and audio, or link videos from sites like YouTube and Rumble. Step one: Register a domain name for a year or two. Best place to do this is the granddaddy of all domains, Network Solutions. where the cost may be as little as $5 or $10. Once you've registered a .com/.net/.biz (there are over 500 domains), it's exclusively yours. Trick is to find a suitable name that's not in use. Just type names into your browser until you get a "Can't Find the Server" failure, which means it's available. Register it, and you now have a domain.

Step two: Build a web site. Designing, editing and updating your site is pretty easy, once you get the hang of it, but initial setup might best be left to a web designer who knows all the tricks - unless you're willing to wade into it and learn how yourself. We don't do web design here (aside from our own sites), but if you keep it simple and avoid exotic/expensive design apps, it isn't difficult.

You can create a mock up site in TextEdit or Keynote to get an idea of how it should look and work. It's all done with text, with instructions to the browser enclosed in angle brackets (<>). You can actually design it all in a word processor, then drag the document into a browser window (Safari) and see how it acts. Once you have a basic layout, translating it into a web-friendly site can be fairly easy. Cruise around the Web for ideas, look at different layouts and site designs, and work on a layout that suits you. Then launch into the real thing with a simple web design app. Step three: Find a web host - or setup a server (very expensive). This is the tricky part. Avoid giant and expensive hosts like GoDaddy and Wix that might hold your site hostage with charges for access and changes. A search for web hosts will produce thousands of 'em, near and far, costly and cheap. Best price with a good reputation, fiber optic speed and no frills is the magic combo. Check out who hosts respected sites you know, especially sites specializing in your particular interest.

Domain names are registered according to the extension attached, with ".com" being the most prevalent. Many ISPs will snag a domain name for you the instant it becomes available, for a small fee - but you might be better off doing it yourself. Domain names become quite valuable when you consider printed materials, investment in site resources, email addresses, and advertising. Read on for more about Domain Name Services.....

|

A capsule history of the Internet In its early, tumultuous life, the "web" morphed from Dr. Jon Postel's DARPA model under the U.S. Department of Defense - a redundant network of nodes - to a thriving, international, global network of networks. To its credit, the Federal Government took a hands-off approach thru the late '90s, avoiding any "internet governance" and only addressing Domain Name Services (DNS) as necessary to facilitate internet operation on a global scale with respect to borders, languages and technology. The model for control of the Internet's entire addressing scheme changed periodically as agreements between governments and multinational corporations were renegotiated, and countless new categories were created, such as .info and .biz domains.

In 1997, the U.S. Department of Commerce was directed to privatize DNS in a manner that would increase competition and facilitate international participation. Thru a cooperative agreement between the National Science Foundation (NSF) and Network Solutions Incorporated (NSI), a fee structure was established for DNS registration and management via NSI's Network Information Center (aka, the interNIC) which was later purchased by VeriSign. DNS is all about the registration of names we use to identify and locate web sites (whatsit.com) with their actual numeric designations (888.88.88.888). IPv4 protocol uses 32-bit addresses in the familiar "dot-quad" format, while IPv6 uses 128-bit addresses in hexadecimal code.

Here in the U.S., our root DNS registry is under license from the U.S. Department of Commerce National Telecommunications and Information Administration, the NTIA and the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority, the IANA. The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, ICANN, certifies specific registrars to sell and manage domain names. These registrars are private-sector corporations (including VeriSign and those listed below).

Top Level Domains (TLDs), also known as Root Zones Country Codes (ccTLD).

Country code domains were originally two-letter suffixes assigned to about 250 countries, but the list is now mixed in with other "Root Zones" which include all manner of corporations, businesses, and individual companies, world-wide.

Generic (gTLD) Domains were also rolled into Root Zones.The largest of these, by far, is still the .com domain owned by VeriSign. The original (short) list of domains below still exist within hundreds of other Root Zones, tho some may have little resemblance to their original purpose.

.aero was originally the air transport industry domain, owned by SITA

Infrastructure Domains (.int and .arpa) are used exclusively for internet infrastructure and management. These are operated by IANA..com/.net/.name/, all owned by VeriSign (since January 2002) .org owned by Public Interest Registry (since January 2003) originally a domain for non-profit organizations but has since gone commercial. .biz is still owned by NeuStar Incorporated .coop is owned by DotCorporation LLC .info is owned by Afilias Limited .museum is (was?) the Museum Domain Management Association .pro is operated by RegistryPro, Ltd. .gov is the General Services Administration (U.S. Government) .edu is operated by Educause .mil is operated by the U.S. Department of Defense .travel is now owned by Dog Beach LLC The short list of original domains above dates back to about Y2K, when things were just getting underway. Like the original Country Codes, these Generic Domains are also scattered within the hundreds of modern Root Zones. Current agreements and amendments (most in pdf format) can be found on the NTIA web site: <www.ntia.gov> Registration and Registrar information is available from VeriSign or the American Registry for Internet Numbers (ARIN): <http://www.arin.net/>

NOTE: Alternative networks included: name.space, AlterNIC, eDNS, WWW2, and others.

Current Trends and Transitions Having started with bulletin boards (BBS) over dialup using terminal programs (like the venerable Zterm), internet access is now achieved using any of a number of web browsers like Safari or Firefox. (Firefox is a distant relative of the very first web browser, Netscape.) Standards and protocols are constantly changing and updating, as is everything else these days, with security being a major concern.

The internet had a "gold rush" of sorts in the late '90s - the notorious "dot-com bubble" - when get-rich-quick schemes of all sorts flooded the new internet market. Those ideas which had merit have survived and flourished (eBay, Amazon, Google, to name a few), but the vast majority of early "dot-coms" were so ill-conceived or poorly executed that the period became known for spectacular and costly failures. Many were flat-out cons.

The 'net has also survived a kind of "wild west" period with little or no official regulation or control, thanks in large part to the U.S. government's hands-off approach to internet regulation. One of the most refreshing and powerful aspects of the internet is its wide-open, unregulated, global access to information of all sorts (at least here in the States), but those days are ending as corporations, tech giants and governments begin to apply control and taxation, censoring and regulation.

Domain name registration VeriSign has done well to stay out of the spotlight as the internet continues to sort itself out. Registration of domain names is strictly controlled in some ways - country codes for example - but wide open in others. Registrars range from giant VeriSign (still in control of .com and .net) to neighborhood ISPs acting as local agents. Registration schemes abound. Services offered by site designers, ISPs, and VeriSign itself range from the rock-bottom biannual fee, to substantial (and unjustified) monthly rates charged to the unwary. Registration of a domain name expires at two or five year intervals, to the exact second. If it goes neglected, someone else can buy it. Best to use a reliable registrar and web host.

Your relationship with your web host (and ISP) is important for a variety of reasons beyond just its monthly charge for hosting; it might best be viewed as a partnership. When shopping for a web host, be sure to factor-in your site's use of forms, JavaScript, CGIs, your space requirements and other qualifications. Review service contracts from potential web hosts, along with host's past history, equipment, and additional services offered before making a long-term commitment. Having a reliable host capable of managing a variety of domain issues can be a big plus. Avoid those hosts who limit your ability to post changes or insist on doing it for you (for a fee), and those that charge monthly fees or have additional charges for traffic, editing and access. Most web designers will have a list of host providers they recommend.

Hosting your own web site requires a static Internet Protocol (IP) address, high-speed broadband (minimum 3Mbps, tho that may be too slow in modern times), and a fast server - all of which is possible for those willing to tackle the technicalities. Does it make sense to host your own web site? Probably not, unless you have bigger plans involving dedicated lines, expense is not a concern, or you plan to provide hosting space for others. It takes time, expensive equipment, constant maintenance and updates, backup servers, and a fair amount of technical know how. Not an easy task.

|

SSD at left is a proprietary Apple Gen5 drive. While these are removable, data recovery may require another Mac like the one it was in. (BTW, beware of counterfeit drives.)

SSD at left is a proprietary Apple Gen5 drive. While these are removable, data recovery may require another Mac like the one it was in. (BTW, beware of counterfeit drives.)